By Lindsey Grovenstein

EARLIER this year, the City Council passed a special-use permit for the Salvation Army to build a multi-million-dollar transitional shelter down the road from the Hudson Hill, West Savannah, and Woodville Neighborhoods—that is, if an archeological study provides evidence that the land in question is not part of the original Weeping Time property.

By now most people are familiar with The Weeping Time—the largest auction of enslaved persons in America’s history, totaling 436 men, women, and children, held at the then Ten Broeck Race Course in 1859.

Our knowledge of The Weeping Time is only relatively recent. West Savannah did not discover this piece of harrowing history until 2006, when the Savannah Department of Cultural Affairs under Mayor Otis Johnson’s administration recruited residents and historians to work on a research project titled “Low Land and the High Road: Life and Community in Hudson Hill, West Savannah, and Woodville Neighborhoods.”

Afterwards, residents fought for a plaque to preserve the history of The Weeping Time in West Savannah, a little plot of land stuffed between roads. Enclosed with an iron fence, bushes, and a couple of benches. And since then, it been the site of yearly vigils and events and remains just one out of the handful of historical markers telling the story about enslaved African Americans in the City of Savannah.

Community members in West Savannah have started a coalition to fund their own study of the land in comparison to the City’s contracted researcher. Many residents in the three neighborhoods oppose the special-use permit, although representatives at the Neighborhood Association have expressed approval.

It cannot be contested that our city is in desperate need of more resources for our houseless population. However, the city is also in need of development that is equitable. Considering that the definition of equitable is to “deal fairly and equally with all concerned,” the concern expressed by residents who will be directly impacted by this decision need to be considered.

This is not the first development that this community has had to face. Zoning and other policy decisions have historically been used to negatively impact neighborhoods like Hudson Hill, West Savannah, and Woodville.

So, when the public considers plans, we do not often see what got us to this point of decision-making. What is another rezoning special-use permit? Perhaps it makes sense to put a homeless shelter over there. We see poverty as commonplace as the crepe myrtles that bloom every year: we expect it. Figure that it just so happens that way naturally.

The dilapidation. The blight. The boarded-up windows multiplying with the tall weeds. The gangs and crime and addiction and shootings. The single parent homes and late rent notices.

But if we take a closer look at the actual history of the area, we will see specific local and federal public policy decisions that influenced these conditions. And with that in mind, we should take our present-day considerations more seriously and democratically.

To take this history to the very beginning, the area now known as the City of Savannah used to be home to the Yamacraw tribe. Chief Tomochichi allegedly deeded the site of Savannah and eastwards to James Oglethorpe’s colony in 1733. His tribe kept control of the wetland to the west. They built a new home and they lived there until the chief’s death. In 1757 the Yamacraw lands in West Savannah were given and distributed to the colonies.

Back then, Augusta Avenue was used to connect Oglethorpe’s colony to the Salzburgers’ colony down the road in modern-day Effingham County. A place I mention because I am a direct descendent from the Salzburgers that to this day have a place of history to call their own outside of Rincon at the end of Ebenezer Road. The original church with bricks indented with fingerprints from my ancestors. An old wooden home converted into a museum. Annual festivals on a large, sacred ground.

In 1782, the Vale Royal plantation was established on 1000 acres of land gifted by the Crown. Vale Royal plantation was bounded by the Savannah River, Fahm Street on the east, Augusta Avenue to the south, and what is today West Lathrop Avenue. Within these boundaries lie the modern-day neighborhoods of Hudson Hill and the portion of West Savannah north of Augusta Avenue. African Americans who were enslaved and forcibly taken here were able to use the wetland in familiar ways, with the swamps being turned into profitable rice fields.

The enslaved lived in shacks and huts. Some freed African Americans bought land later on as well. When slavery ended, the plantations eventually did too, and although production rates declined the agricultural nature of the area persisted.

The twentieth century brought a new transformation for West Savannah. A plethora of plants and factories established themselves along the riverfront like the Savannah Sugar Refinery, Mutual Fertilizer Company, Hilton Dodge Lumber Company, and the American Can Company. The Central of Georgia Railways and the ports were also a large employers back in the early 1900s. This growth of industry brought stable, long term jobs for families across racial lines, although, “often industrial plants hired African Americans as laborers at low pay.”

The areas now known as Hudson Hill, West Savannah, and Woodville became home to Black and White working-class residents. In these days, the factories, and later the defense department during WWII, would build subsidized housing and neighborhoods for their employees.

This was of course during Jim Crow-social apartheid, where different races did not mingle much, except for sometimes in working environments such as this. The subsidized housing built was explicitly segregated. White workers had much better living conditions than their Black counterparts, who tolerated inferior quality homes, as well as lower pay and “the constant reminders of second-class citizenship in the small things of life that gnawed away patience.”

Neighborhood amenities included parks and pools open to whites and that were used by African Americans only on a very restricted basis. The schools were segregated and African American children received lower quality education than their counterparts.

There were many small businesses that were owned and operated by both White and Black owners in the area like grocery stores, restaurants, pharmacies, and dry cleaners. Because African Americans were not allowed to shop in the "whites only" area and it was too expensive for West Savannahians to take a bus to West Broad Street (modern day MLK Boulevard) to shop with the middle-class African Americans, they experienced a very close-knit communal way of life.

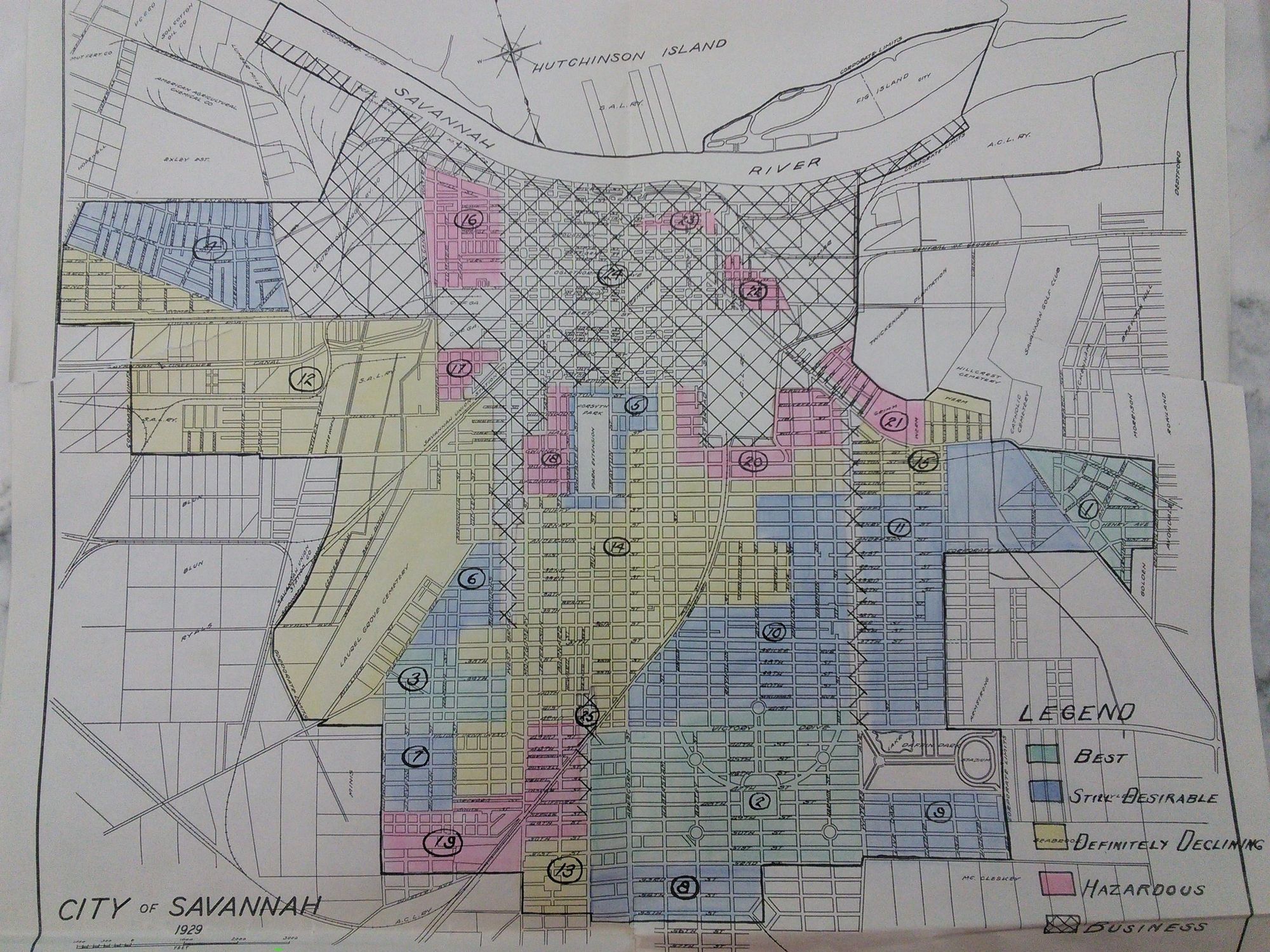

During this time, policies and ordinances were being passed on the federal and local level to further disenfranchise particular areas and support others. In 1934, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) created maps for banks that advised what were "low-risk" or "high-risk" areas to loan money to. This practice was called redlining, and historically across the nation Black and brown and poor working communities were marked in red as “hazardous.” When we look at Savannah’s redlined map, we see an unmistakable trend in socioeconomics that is apparent today based on redlining distinction. The areas that were most heavily invested in then still hold the most value now, and vice versa.

In spite of that, West Savannah remained a close and humbly profitable community until the 1960s. An unintended consequence of Civil Rights was that many West Savannahians brought their business to white store owners in areas like Broughton Street. The small businesses along Augusta Avenue could not keep up with the competition.

Further, integration spurred White Flight. The majority of the previously integrated, working-class white families had fled to surrounding areas to move into subsidized, low-interest suburban neighborhoods. Not just from West Savannah, but from most of downtown. Previously all white neighborhoods were threatened by the aspect of a single African American family moving in. (This caused many violent riots from white neighbors, but we won’t focus on that.) The real estate market scared home owners with propaganda that their home value would plummet from this infiltration of integration.

These reasons, paired with the industrial golden age of our city ending, attributed to the economic downfall of the area. The factories in West Savannah started closing. “The bedrock weakened in the 1970s and crumbled in the 1990s with layoffs and downsizing, the economic health of the community suffered . . . With fewer jobs available, working-age residents, especially young adults, left the area,” says "Low Land and The High Road."

During this time communities were also experiencing the effects of the Great Migration, where millions of Black families moved to the north in search of better conditions.

The aforementioned causes, as well as a specific problem with home ownership rights (there were and remains many abandoned homes whose ownership are contested after the owner died or moved), produced what we now refer to as the ghetto.

In the 1970s the federal government created "slum clearance" practices that were widely in use for local jurisdictions. A major tool in the toolbox of federal "slum clearance" was the U.S Highway System. Across the nation, even in the North where African Americans had migrated to, interstates were being erected in the rubble of Black neighborhoods.

Our own I-16 plummets through many Black communities. The exit near MLK Blvd destroyed the middle-class Black neighborhood Frogtown, displacing community members so that the booming businesses on West Broad disappeared too. Many other prominent neighborhoods were destroyed in the process.

A 516 exit off of Augusta Avenue will take you right to the parcel of land in question. The land was home to public housing that was demolished due to deterioration. (Another systemic blow: once housing was established for the middle class, the FHA’s budget slowly decreased so that they could no longer maintain the current projects they handled.)

Into the 1990s and up to 2008 the banks were finally allowed to lend to low-income areas, but at exurbanite rates. Predatory lenders became common practice. Many poor people were targeted for "subprime" mortgage loans, which were the catalyst for the housing crash in 2008 that left many homeowners on the street.

Present day, these areas that have been put through the public-private ringer are now offered to investors at low interest rates for new development projects meant to “revitalize” the depressed neighborhoods.

In the book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothestein argues that federal and local governments have systemically and intentionally segregated cities. Many Americans assume that segregation is de facto, a product of individual choices and market conditions. These examples and many more prove that segregation is de jure, a product of unconstitutional and intentional policies.

Racism’s effects can be felt in every area of life. I have only touched on systematic racism as it pertains to housing. To describe other institutions would be another project, but a similar path can be traced through other systems like the judicial and educational sector. All of these cumulate to our modern-day conditions. This is the work of anti-racism, to recognize these patterns and address it. The intentional act of undoing the residual effects of racism.

Zoning and ordinances have been used as a tool to explicitly oppress communities of colors. Issuing a special use permit to rezone a residential area should spark legitimate concern for conscious citizens.

Considering that much of the West Side is zoned for industrial and commercial use (another intentional tool of segregation) the neighbors that have remained are fighting very hard to reinvigorate the area for residential use, to bring about a revival of close neighbors and small businesses along the streets like there once was. To build parks and pools and other amenities that are free for all residents, and not made especially for tourists. To establish schools and hospitals and other public services. To honor their ancestors and create a healthy and safe neighborhood for future generations.

The decision leaders make regarding the use of this land will shape the way that the rest of the land is used. I imagine that residents who have grown up there, who hold a legacy and more history than we know in their hands, who have so much capacity, want nothing more than the privilege that my ancestors have in Ebenezer: a sacred place and home to call their own and the liberty to choose what to do with it.