THIS MONTH MARKS THE 30th anniversary of the publication of John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, in 1994.

Everyone is already putting out their often-predictable retrospectives. I figure mine might be more worth your time since I actually knew Berendt and many of the people in “The Book” personally, literally as it was being written.

The first thing to know – and I’m not making this up – is that my mom was John Berendt’s travel agent, while he was researching and writing what would become Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

I shit you not.

What’s a travel agent, you ask, if you’re under 40? Well, no one bought airline tickets online during the mid-1980s when Berendt was researching Midnight, for the simple reason that it was impossible to do so. Google tells me the first airline ticket sold online was in 1995.

Back in the day before everyone carried the internet around in their pocket, you either called the airline directly to buy a ticket – and talked to a real person! – or you talked to your local travel agent, who had the correct primitive computers on hand, hooked up to all the airlines’ ticketing systems via grayscale screens and floppy discs. Travel agents like my mom made their money through the small commission on each ticket.

So like I said, my mom, Elizabeth Morekis – Bettye to her friends – handled John Berendt’s flight arrangements during most of the time he was flying back and forth from New York to do research on what would become Midnight.

Why does this matter?

Not at all coincidentally, my mom also handled flight arrangements for many of the selfsame real-life characters who would later become characters in Berendt’s book.

Was my mom Bettye in her own quiet, uncredited way, the human catalyst that made “The Book” possible in the first place, by bringing together into her colorful social world this veritable circus of eccentrics and ne’er-do-wells who formed the core of downtown Savannah’s social and cultural life?

Maybe, maybe not. But that’s a story for a different time.

As I recall, it all went down something like this:

MY MOM’S travel agency, called America Travels! – with an exclamation point! – was located downtown in what you might recall as the former Bergen Hall at MLK and Zubly, once the home of SCAD’s now-defunct photography program.

At the time, however, it was a somewhat schlockily and hastily rehabbed building dubbed “The Atrium,” and my mom’s travel agency occupied the bottom floor.

To get a sense of the time as well as the place, remember the events I’m describing now all happened in the mid-to-late 1980s. This is actually the period of time when Berendt was researching The Book.

As Berendt has said, he wasn’t actually present in Savannah during the period when Jim Williams first went on trial (an eventual four times!) for the 1981 murder of Danny Hansford. Berendt didn't even make his first visit to Savannah until somewhere between the second and third trials.

This was long before the umpteenth “streetscape” of Broughton Street, long before The Lady and Sons, long before social media and Airbnbs and Uber. In The Book, SCAD is described as having 700 students. Today, it’s at least ten times that number.

Downtown Savannah was in some ways a grittier place, but in other ways safer and friendlier, with a much more communal feel. The streets were filled with everyday people who actually recognized each other, and the few unhoused people present were mostly celebrated, even looked after, as colorful characters.

Contrary to popular opinion, plenty of tourists did come to Savannah in the ‘80s – but it was mostly regional tourism. The big tourism boom didn’t happen until after Midnight itself was published, and Savannah became a nationally and globally recognized name for the first time.

Back then, my mom got her travel business the old-fashioned Savannah way: by being very nice and polite and helpful. And hosting awesome parties.

Awesome parties at the travel agency.

Simply put, we had a ritual of holding a regular Wednesday evening happy hour there in the office on what was then called West Broad Street, now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Clients and friends – the line between the two was blurred at best – would gather and drink booze in the office and socialize.

Like I said, business the old-fashioned Savannah way.

Did my mom ever get a permit or a liquor license to serve copious amounts of alcohol to clients in The Atrium? In two words, fuck and no.

This was Savannah in the Big 80s. Permit, shmermit. Have another drink.

As the Midnight character Joe Odom himself says in The Book when he’s about to get in trouble for guests drinking cocktails during tours of the Hamilton-Turner House:

“‘The law says I can’t sell liquor,’ he said. ‘It doesn’t say I can’t serve it.’ Somewhere in the grey area between selling and serving, Joe knew how to make money giving liquor to his customers, and he went right on doing it.’”

SO THIS was the milieu that John Berendt literally landed into as he came to Savannah. Even the travel agency here has a happy hour, he’s thinking to himself.

I first met Berendt at one of these office cocktail parties. I was attending the University of Georgia at the time, and would frequently bop back and forth between Athens and my hometown of Savannah. I was in the journalism school at UGA, so Berendt and I found a good bit in common to talk about.

Over drinks at the busy office party on West Broad Street, Berendt explained to me exactly what he was doing, and what the goal was: He’d become fascinated by Savannah and was going to write a book about real life here.

While he was clearly intrigued by the many colorful and interesting characters he’d met so far, I also got the strong sense that he had become disillusioned with the rat race of the writing/publishing scene in New York, which I vividly remember him describing to me as a “nest of vipers.”

That line stayed with me for years, and I suppose it subconsciously influenced my future career choices to some extent.

My sense was that in Savannah, Berendt had found a group of people who, for all their other faults, weren’t as cutthroat or treacherous. He had a genuine fondness for the city and its people.

I remember he interacted with folks at my mom’s parties as if he’d known them a long time, and didn’t in any way come across as arrogant or looking down his nose at them.

Berendt was keenly observant about human nature – a skill his book would later reveal to great effect – and I could often see the wheels moving in his head as he listened to people. But at no point did I sense judgment.

The thing I’ve always loved about Berendt and Midnight is that, first and foremost, he was a reporter. And Midnight is in the final analysis an excellent work of reporting.

Berendt has since described Midnight as “faction,” a combination of true-life and embellishment. He has admitted, and it’s obvious that, many portions of the book consist of imagined or reconstructed conversations and encounters.

There are many things that, frankly, Berendt couldn’t possibly have witnessed because he wasn’t there, or they had happened years in the past.

But all that said, Berendt’s focused, laser-like powers of detail and description together with his adamant refusal to patronize his characters are, I feel, his chief accomplishments.

I’m certain that his writing style ended up having a profound effect on my own, albeit not by deliberate imitation.

A MAJOR presence at my mom’s office cocktail parties was none other than Joe Odom, one of the lead characters in Midnight. His law office was upstairs from the travel agency.

I recall that he was every bit as affable and gentlemanly as Berendt describes. A wry sense of humor, a legit expert jazz pianist in his own right, a skilled ballroom dancer, and actually a physically large and fairly imposing man as well.

Joe’s reputation as a notorious check-bouncer, an important part of Midnight’s narrative, was already a well-known chapter of Savannah mythology. He had in fact bounced more than one check to my mom for his airline tickets.

So why was Joe still welcome at my mom’s parties despite being basically a grifter?

You probably guessed already: Joe Odom knew a shit ton of people who often needed airline tickets and who wouldn’t bounce their checks. People like John Berendt.

And he happily insisted that they all use my mom’s travel agency.

I believe in business management that’s what’s called a “loss leader.”

One office party was particularly memorable. My sister Christina made it a surprise birthday party for our mother. We surreptitiously wheeled in a piano and Joe played for the large crowd, which probably included a dozen or so people who would end up in The Book.

I don’t think I ever saw my mom happier than that evening.

This in a nutshell explained not only Joe’s appeal as a character but sheds much light on Savannah itself, as I’m sure Berendt would agree.

I KNEW and met plenty of other people catalogued in Midnight, some pretty well and others more in passing.

The late Wanda Brooks, who passed away just last October, was a good friend of the family apart from her connection to the Midnight coterie. She was part of that downtown hardcore who adopted the bars at 1790 and McDonough's as second and third homes, as did many characters mentioned in The Book.

She was exactly as Berendt describes her, down to the ever-present dangling cigarette miraculously glued to her lips and her habit of bumping into people and spilling either her drink, or theirs, or both.

After Midnight’s publication she would often introduce herself to people simply by saying, “Wanda Brooks. Page 84 of The Book.”

And as described, she actually did often make her entrance into a bar with someone, often Odom himself, playing “New York, New York.” In later years she had cleaned up her act and gotten into real estate, where her charisma and flair for publicity worked to great advantage.

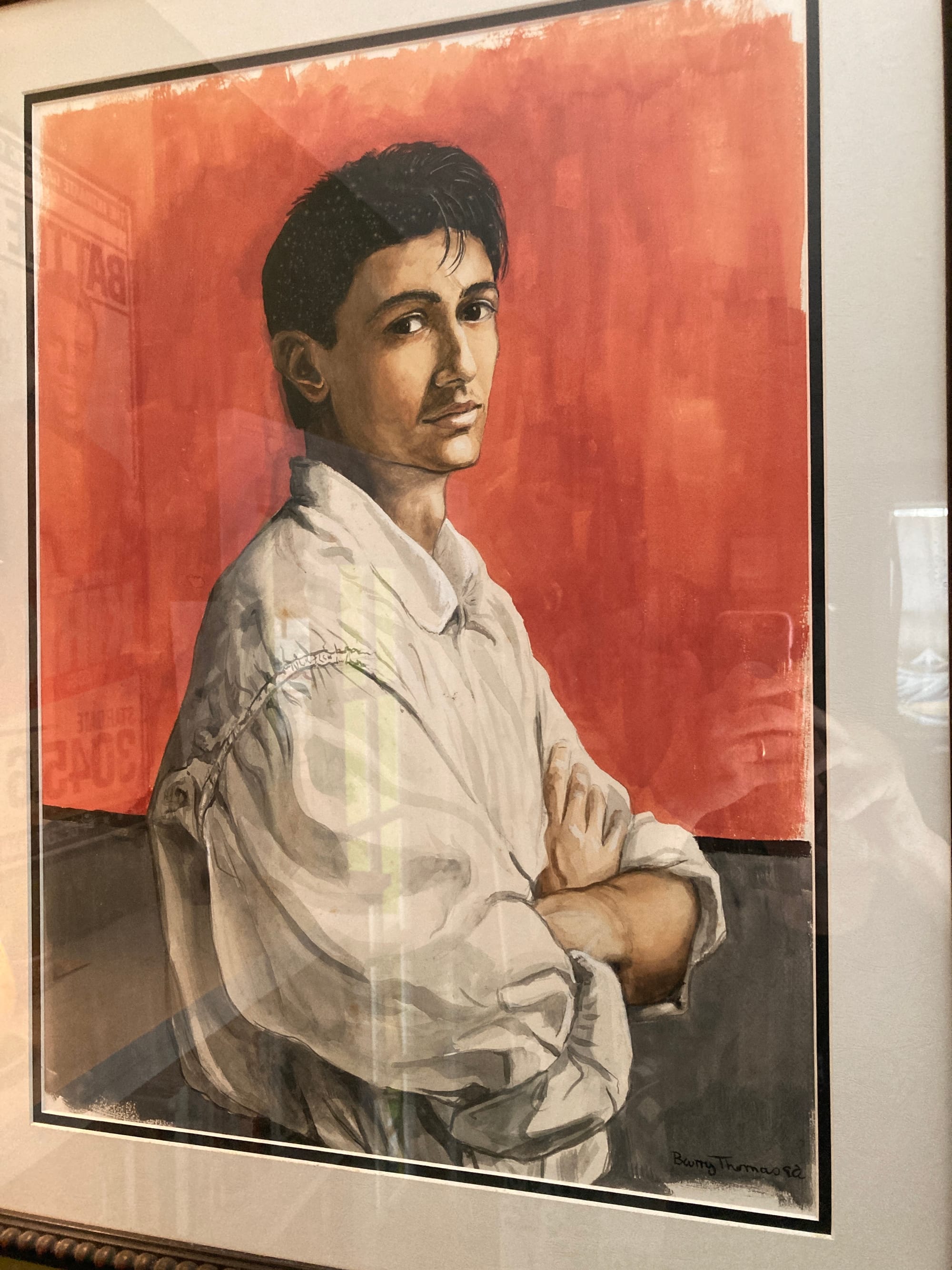

Barry Thomas, Jim Williams’s longtime assistant and furniture preservation/rehabilitation expert, is mentioned several times in The Book, often in embellished passages that Berendt couldn’t possibly have been witness to.

Thomas was literally – and again, I’m not making this up – the Best Man at my first wedding. He had been good friends with my now-former wife Lisa. At one point we actually traveled to his native Scotland and met him and his family in Glasgow.

As you gather from the way he's described in Midnight, Thomas was very sweet-natured and not prepared for the whirlwind of publicity and notoriety stirred up by the Hansford killing and the multiple trials – during which Thomas continued to run Williams’s business even as his boss was behind bars awaiting retrial.

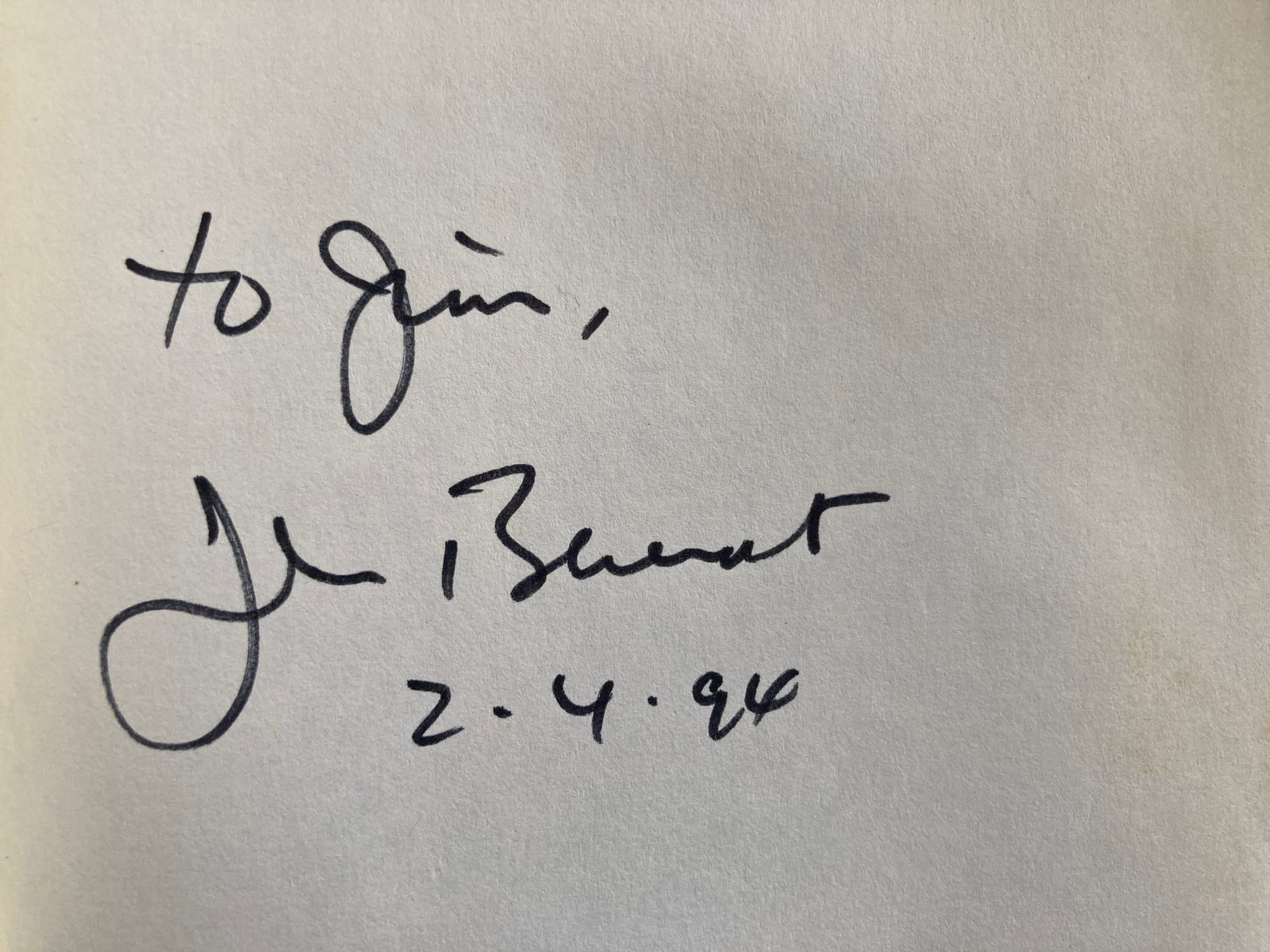

He preferred to renovate furniture, and most of all to paint. I still have a watercolor portrait of me he painted. He’d never done watercolors before, but wanted to learn in a risk-free environment before offering his portraiture services to rich clients. So he offered to give me the portrait in exchange for me sitting for it.

Tragically, my friend and portraitist Barry Thomas passed away from HIV/AIDS in 1992 at the young age of 38.

He died two years after Jim Williams himself would also pass away from HIV/AIDS, and one year after Joe Odom died of the same horrible affliction.

Indeed, the most salient political and social subtext of Midnight – subtext because it’s not mentioned in The Book – is the fact that so many characters passed away in such a short period of time from the scourge that was AIDS, prior to the widespread use of effective medication that we take so much for granted today.

IN MIDNIGHT, Berendt describes Joe Odom accurately except for one little thing, as has been noted elsewhere.

Odom was not in fact the lady’s man portrayed in The Book and was not in fact romantically involved with “Mandy Nichols” (real name Nancy Hillis, who passed away in 2016).

Joe Odom was in fact a fairly widely acknowledged gay man. Berendt has occasionally come under fire for this somewhat revisionist history.

The simple truth is that most of the main characters in Midnight were LGBT: Jim Williams; his lover Danny Hansford (who was certainly bisexual); Joe Odom; and The Lady Chablis.

Was a decision made in the “viper’s nest” of New York publishing that at least one of the main characters had to be portrayed as heterosexual for marketing purposes, in a time with much less mainstream awareness and acceptance of LGBT people? I don’t claim to know the answer, but this has been the subject of speculation, and criticism, for years.

While it’s clear that much of Berendt’s time here involved delving into what has been salaciously called Savannah’s “gay underworld” – much of which didn’t see the light of day in the final version of The Book – it’s also clear that someone, somewhere along the way decided not to make gay life in Savannah literally the whole point of Midnight.

In the wake of the Lady Chablis’s death in 2016, many capable think-pieces were published exploring her contribution to the humanization of trans rights and trans awareness before this was even a widely acknowledged fact of life in America.

While today we would identify Chablis as transgender, that wasn’t remotely close to a generalized or normalized term when Midnight was published. The now-antiquated terms “transsexual” or “transvestite” were often still employed, and in The Book itself Chablis is identified specifically as a drag queen.

However, Berendt almost seems to peer into the future in one section when he describes Chablis thusly:

And she was definitely a she, not a he. I felt no tendency to stumble self-consciously over pronouns in her case.

I suppose you could say this is pretty prescient language for 1994. In any case, Berendt’s deeply sensitive and empathetic portrayal of The Lady Chablis, and his refusal to make her the butt of cheap jokes or moral grandstanding, is just one reason Midnight still holds up so well, 30 years later.

AS A NATIVE SAVANNAHIAN myself, I’m always amused that people tend to sum up Midnight as some kind of inner look into the secret lives of old-time Savannah people.

The truth is there aren’t that many native Savannahians in The Book at all. Almost all characters of note came here from somewhere else. And that’s key.

Jim Williams from Gordon, GA. Joe Odom from Claxton. Emma Kelly from Statesboro. Nancy Hillis from Tennessee. Lady Chablis from Florida originally, growing up in Chicago, Harlem and Atlanta.

Even little Barry Thomas all the way from Scotland.

Most of the actual Savannah natives in The Book are either lawyers, like Sonny Seiler and Spencer Lawton, or members of various exclusive clubs like the Married Women’s Card Club or the Oglethorpe Club or the Chatham Club.

The main characters came here from somewhere else… striving to start their own clubs. Striving to recreate themselves. Striving to fit into a place they’re not from, a place notorious for not letting outsiders fit in.

And this, I think, is the real underlying message of Midnight: That Savannah is a state of mind.

That people are drawn here because of the person they hope to become, or perhaps, the new person they can create from whole cloth.

I think we all know that person who just moved to Savannah a few years ago from Anytown USA and has already adopted what they think are all the "right" attitudes to fit in locally.

You know, the people who have barely unpacked their bags but all of a sudden start saying things like "I just refuse to go south of Derenne" or "we don't go downtown anymore, too many tourists."

This is a theme Berendt lays out literally from The Book’s first page!

The opening scene is Jim Williams talking to Berendt inside the Mercer House on Monterey Square. His very first line in The Book is:

What I enjoy most is living like an aristocrat without the burden of having to be one. Blue bloods are so inbred and weak. All those generations of importance and grandeur to live up to. No wonder they lack ambition.

It’s both a scathing take on the milieu he finds himself living and working in, as well as a direct challenge that none of your fucking aristocracy matters in the end – I’m going to force my way in and change your rules from the inside.

Which Williams does throughout the course of The Book. Which is a thoroughly…. American thing to do.

The subtitle of Berendt’s book is “A Savannah Story.”

I would submit that it’s a distinctly American story as well.

SO WHAT was the actual impact of Midnight on Savannah, especially its tourism industry? You don’t need me to tell you the impact was huge. Like really huge.

But then again… maybe it was also a question of timing.

As others have pointed out, The Book’s publication came exactly at the time when the U.S. economy was hitting peak performance. In the mid-1990s everyone could get a good job who wanted one, the markets were constantly going up, and the U.S. wasn’t involved in nearly as many stupid wars on the other side of the globe.

In short, Americans had a lot of disposable income in the mid-1990s. And one thing they wanted to spend that money on was traveling.

Enter Midnight and its stupendously long run on the top of the New York Times best-seller list. While ostensibly a work of true-crime reporting, let’s face it: Midnight is a hell of a travelogue, published at exactly the right time for maximum effect.

The Book would have boosted local tourism in any era. But you can make the case that, had it come 20 years sooner or 20 years later, larger economic conditions might have muffled its impact.

However, the most intriguing explanation I’ve heard comes from none other than former County and Interim City Manager Patrick Monahan. As I reported, in a recent presentation to the Chatham County Commission he put forth an interesting, and I believe accurate, assessment.

It has to do with paper mills.

For folks newer to town, you need to know that prior to the 1990s the huge paper mill adjacent to downtown now called International Paper – it was Union Camp back then – fumigated the entire city of Savannah, and indeed the whole area for many miles around, with a thoroughly disgusting odor of rotten eggs.

While local Chamber of Commerce types often called it “the smell of money,” it was actually a fetid, nausea-and-rash inducing, 24-hour-a-day stench that actively and aggressively drove investment, especially tourism investment, away from Savannah.

It’s no coincidence that when a ritzy new gated subdivision called The Landings was proposed to house Union Camp executives away from Savannah’s unwashed masses, it was located on Skidaway Island – literally as far away from the paper mill within Chatham County as possible.

But as Monahan points out, in the early 1990s Union Camp was essentially forced to spend many tens of millions of dollars on a “scrubber” – a device to extract most of the disgusting sulfur dioxide particulates from the paper mill’s smokestacks.

While it was surely coincidence that Midnight was published just as the local air was noticeably cleaner and easier to breathe, Monahan directly credits the scrubber with the larger picture of a sustained tourism boom to Savannah that would last long after The Book dropped off the best-seller list.

WITH THE death of Jim Williams’s lawyer (and UGA mascot owner) Sonny Seiler last summer, all the main characters in The Book have passed away, along with most of the minor characters as well. Even Jack Leigh, the phenomenally talented photographer who captured the iconic Bird Girl image on the cover.

As I noted earlier, both Williams and Odom died before Midnight was even published, though Berendt leaves that out of the narrative.

While you will read in some misguided pieces that only Berendt himself survives, that’s not true. Spencer Lawton, the former Chatham County DA who secured three convictions of Williams only to see an Augusta jury finally acquit him for good, is still alive. Cora Bett Thomas, who gets a brief mention, is still with us.

Jerry Spence is still very much alive, though one is never quite sure where you’ll see him next.

And while it’s not a human character, let’s not forget that Club One is also still very much a going concern.

INDEED, WHILE the usual boring topic is how much Savannah has changed since The Book, I prefer to focus on the many things about our city Berendt chronicles that haven’t changed at all, for better or for worse:

- Like how perfect our city plan still is. As Mary Harty is quoted, “The thing I like best about the squares is that cars can’t cut through the middle; they have to go around them. So traffic is obliged to flow at a very leisurely pace. The squares are our little oases of tranquility.”

- Like how Savannah still celebrates eccentricity: “Every nuance and quirk of personality achieved greater brilliance in that lush enclosure than would have been possible anywhere else in the world,” Berendt concludes.

- Like how the movie business still takes advantage of Savannah. As Jim Williams says: “Savannah doesn’t get publicity after all, because the audiences usually haven’t the vaguest idea where the movies have been shot… the costs to Savannah turn out to be greater than the return, if you add up the overtime pay for sanitation men and police and the disruption of traffic… one crew even cut down a palm tree across the square, because it didn’t happen to suit them.”

- Like how Congress Street is still where the party is, whether at The Pickup in Midnight, or The Rail or Social Club now.

- Like how no bridge over the Savannah River is ever tall enough. “More ominous yet, it seemed that Savannah’s most lucrative source of income – the shipping business – was on the verge of being choked off by, of all things, the old Talmadge Bridge.” That bridge – the route Jim Williams takes to see Minerva the Root Doctor in Beaufort – was demolished before The Book was even published, because it was too low for the cargo ships. The one there now that replaced it is already considered too low.

- Like how Savannahians still don’t go to Charleston very often. “But then Savannahians rarely went anywhere at all,” Berendt narrates. “They could not be bothered.”

- Like how fucking cheap people still are in Savannah. As Williams says, “When I find an especially fine piece of furniture I send a photograph of it to a New York dealer. I don’t waste time trying to sell it here in Savannah. It’s not that people in Savannah aren’t rich enough. It’s just that they’re very cheap.”

- Like how preservationists still squabble among each other and argue about what gentrification means, and claim to be saving downtown when they prefer to live in Ardsley Park.

- Like how Savannah still falls for charming raconteurs like Joe Odom, who steal your heart and your money with a smile and a song.

- Like how tour guides still just make shit up.

- Like how people here still love to have a good drink and a good time. “Parties became a way of life, and it’s made a difference.”

- Like how St. Patrick’s Day is still our “high holy day.”

And like how stunningly, timelessly beautiful Bonaventure Cemetery truly is, at midday… or at midnight.