THE SURPRISE NEWS of the imminent closure of the massive International Paper mill after a nearly century-long presence on the Savannah River hit the local community last week like a sledgehammer.

The closure of both the Savannah and the Riceboro mill in Liberty County was announced via a dry corporate press release droning on about "aligning resources" and "positioning International Paper for long-term success," among other buzzwords.

The harsh reality is that about 1000 Savannahians will now be laid off, with the mill scheduled to close at the end of September.

While the human cost of the layoffs is clearly and rightly the thing uppermost on local minds, let’s delve into the history and impacts, positive and negative, of International Paper in Savannah – formerly Union Camp, formerly Union Bag – and then weigh the scales accordingly.

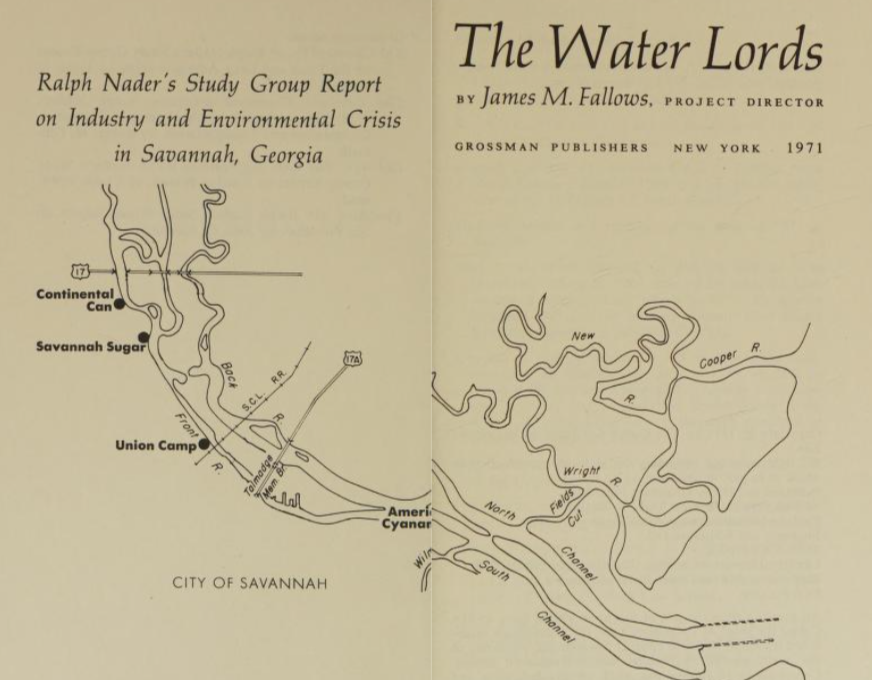

Old heads in Savannah will remember the impact of a seminal environmental 1971 book called The Water Lords, by James M. Fallows, based on research by a Ralph Nader study group.

The Water Lords – every bit as required reading for a Savannahian as Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil – tells the true story of what happened when the New York-based Union Bag came to Savannah during the Depression era with the promise of many jobs.

What would Union Bag get in return? Just about everything.

Paper mills use a truly stunning quantity of water in the process of making paper from wood pulp.

So Union Bag would get the sweetheart deal of sweetheart deals: Basically unlimited, nearly free use of the greatest natural resource we possess in this region, water from the Floridan Aquifer.

The Floridan Aquifer is essentially a vast underground limestone cavern that stores fresh water that seeps down into it over millennia from the hinterland.

Some of the water in the Aquifer is 10,000 years old, the descendant of rains that came down on Appalachia at the dawn of history.

The beauty of the Aquifer is that due to the filtration process of the limestone, no treatment is necessary – it comes out of the ground fresh and pure and free of germs and bacteria.

The other beauty of the Aquifer is that the internal water pressure – assuming it stays intact – is a natural barrier to saltwater intrusion.

Unless…. the Aquifer is overpumped, and then it can become salinated as its pressure decreases. When a water source is salted out, it’s salted out – you can’t drink from it anymore without treatment.

Salination of the Aquifer mostly due to the paper mill is precisely why the City of Savannah this century had to supplement our drinking water with treated water from the Savannah River, while the paper mill continued to use Aquifer water for next to nothing, as it had for decades.

By the mid-1950s Union Bag merged with New Jersey-based Camp Manufacturing to form Union Camp, the name by which the paper mill was known to most current Savannah natives. (International Paper bought the mill in 1999.)

The other thing paper mills are known for other than prodigious water use is their equally prodigious stench.

Those of us who grew up in Savannah in the 1970s, when The Water Lords was published, remember the odor vividly.

It’s like rotten eggs, only much stronger. And this smell of rotten eggs gives you a rash all over your body if it’s thick enough, and doesn’t ever completely come out of your clothes.

Generations of Savannahians slyly called the horrible stench “the smell of money,” due to the many comparatively good-paying jobs the paper mill created.

But “the smell of money” was also the smell of pollution that damaged the lungs and internal organs, as well as the smell of a huge damper on less environmentally harmful types of economic growth.

It’s no coincidence that when a ritzy new gated subdivision called The Landings was proposed to house Union Camp executives away from Savannah’s unwashed masses, it was located on Skidaway Island – literally as far away from the paper mill within Chatham County as possible.

Believe it or not, the smell of the paper mill is much, much better today than it was when we were growing up here.

What happened? A scrubber happened.

Former County and Interim City Manager Patrick Monahan has explained the entire situation best. In a presentation to the Chatham County Commission last year, he put forth an extremely interesting, and I believe accurate, assessment.

Monahan’s theory is that when Union Camp was forced to pay nearly a billion dollars to put the “scrubber” on the Savannah plant in the early 1990s to remove the fetid sulfur dioxide stench from its smokestacks, that was the real harbinger of the tourist boom that would come.

There would be no Midnight boom, no Paula Deen boom, no SCAD expansion, the theory goes, without that horrible smell finally being largely eliminated from the downtown air first.

That is one more measure of the impact of the paper mill on Savannah, above and beyond its job production.

If you want to get a sense of how bad the smell was, you could travel down to Riceboro in Liberty County over the next few weeks, while that plant is still open.

Or you could go to downtown Brunswick, Ga., where a similarly massive paper mill owned by Georgia-Pacific churns out its disgusting cloud of rotten egg smell 24-7, directly adjacent to that city’s historic district.

I’m sure that’s at least one reason why downtown Brunswick – which originally had the same Oglethorpe town plan as Savannah – has remained so stagnant economically.

So the closure of the Savannah paper mill is the end of an era in lots of ways – historically, economically, and environmentally.

The job loss is devastating, especially at a time when the U.S. economy appears headed for systemic layoffs due to a variety of factors, including tariffs and AI.

But environmentally, the verdict is as clear as water from the Floridan Aquifer: The local water supply and air quality is much better off without it.

Of course you don't really get a break with capitalism, and International Paper is shutting down its water use in Savannah just as the Hyundai Metaplant is ramping up its own use.

The massive EV plant in Bryan County – the largest single economic development in Georgia history – is expected to use at least 4 million gallons of freshwater per day, as much as the entire population of Bryan County uses.

But this contrasts with International Paper's roughly 40 million gallons per day, an exponentially higher stress on the Aquifer that will now go away.

International Paper says it is providing severance packages to laid-off employees. And local leaders have expressed enormous sympathy, but not much else, for their plight.

As for what happens to the literal paper mill and the land it now occupies, one assumes it will eventually become another berth for Georgia Ports Authority, after extensive environmental cleanup.

But that will be another tale of another massive environmental impact, for another time.