IT seems like so long ago. So much has happened in this country and in the world since 2023, when a local grassroots victory successfully changed the name of Savannah’s Calhoun Square to the name it’s known by today: Taylor Square.

The old name honored a strong advocate of slavery, who had no background in Savannah at all. The new name honors Susie King Taylor, a local Black educator born into slavery, who became the U.S. Army’s first Black nurse.

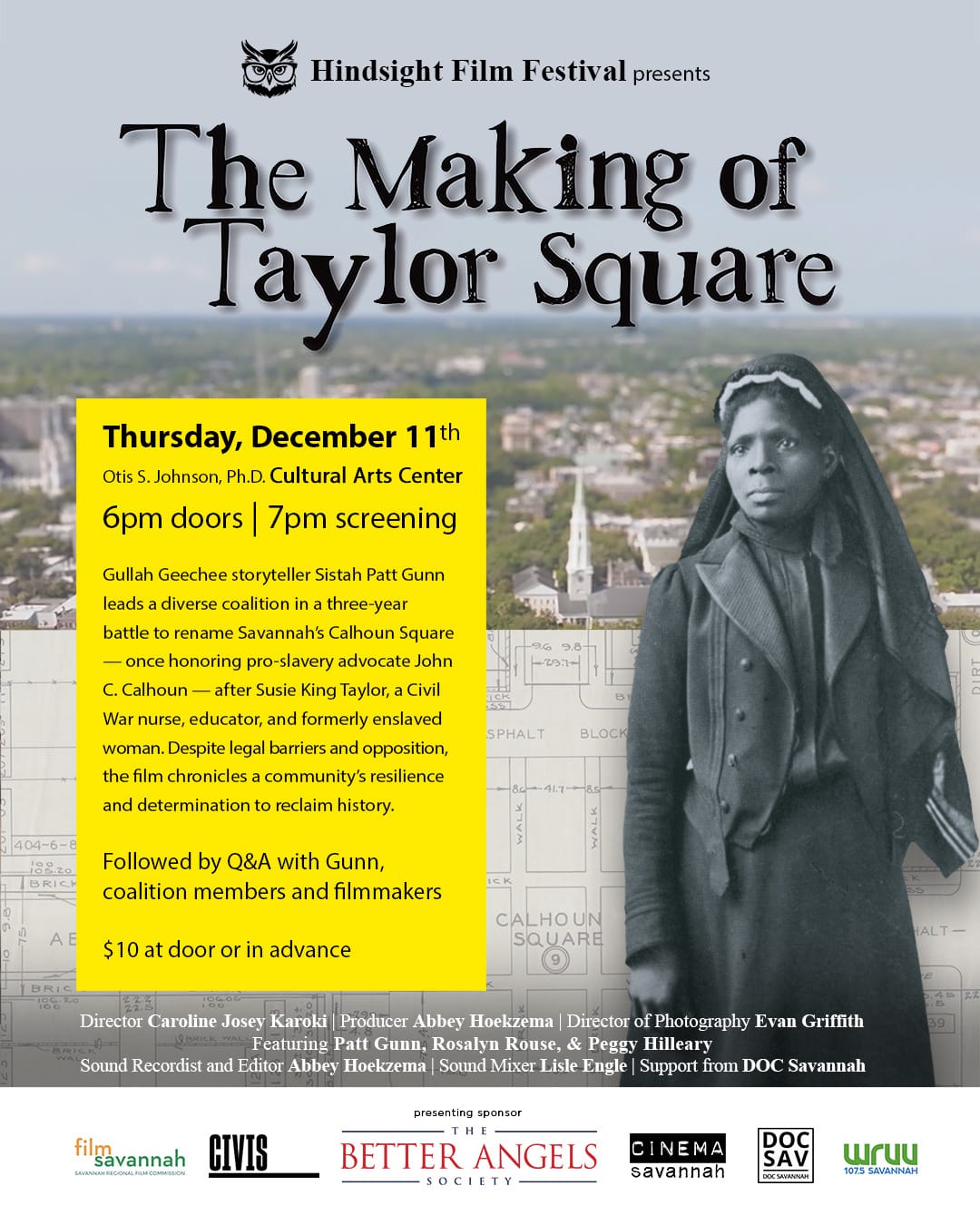

A new documentary, The Making of Taylor Square, screens this Thursday night, Dec. 11, at the Otis Johnson Cultural Arts Center downtown, courtesy of the locally-run Hindsight Film Festival, dedicated to the art of the historical documentary.

It was quite a process, to change the historic name of one of Savannah’s fabled squares. Due to the nature of our town plan – where residences directly overlook these cherished greenspaces – permission had to be gained from a majority of residents on the Square Formerly Known As Calhoun.

On the surface the “stars” of the show are the Savannah women responsible for the historic effort: “Sistah Patt” Gunn and Rosalyn Rouse. The pair often work together on their popular Underground Savannah tours highlighting local Black history.

But the real stars, they say, are the community members who supported them, and got fully behind the effort.

The short film documents how efforts began during the pandemic to raise awareness of Calhoun’s prominent national role in encouraging not only slavery itself, but the continued spread of slavery in the United States.

From there, Gunn and others mobilized public opinion, local government, and concerned residents to finally make the change happen a couple of years ago.

But according to Sistah Patt herself, the credit goes to the community. The thing she is most proud of is the example she and her fellow activists have set for young people.

“This represents a blueprint for a new generation to be able to overcome opposition to renaming any school or street or public space,” Gunn tells The Savannahian. “This is a model for civic engagement.”

“The working title of this film was actually ‘How To Rename a Square,’” interjects Pat Longstreth, a local documentary filmmaker who runs the Hindsight Film Festival and who helped organize this screening.

Gunn explains some of the internal politics that led to the change:

“We met with the City Manager (Jay Melder), and mentioned that they had already done all this in Louisiana, where he’s from. They ordered every Confederate monument to come down in New Orleans and by the next Monday they had all come down,” Gunn says.

“We reminded him that according to our city charter and governmental structure, as City Manager he had the power to do this. And we were able to get it done under his guidance as City Manager.”

The way Gunn explains it, the key to the success of the name-change was in not pushing for it all to happen in one move.

First, she says, the Calhoun name needed to be stripped by local government. That process was aided by getting that issue officially put on the City Council agenda.

Then, the renaming was left up to the community in a voting process. The winner, Susie King Taylor, was born into enslavement in Liberty County. After moving to Savannah as a child, she attended two secret schools – literacy and education being illegal for enslaved Black people to pursue here at the time.

During the Civil War, Taylor became the first African American U.S. Army nurse, after escaping and joining up with the Union Army.

During Reconstruction, Taylor opened two schools in Savannah and one in Liberty County. She would also publish her Civil War memoir, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp.

Gunn repeatedly says she is finished with any further efforts to rename public monuments and spaces in Savannah.

One of her goals – removing slaveowner George Whitefield’s name from Whitefield Square – remains unrealized, though there is an effort underway to research a historic Black burial ground alleged to be underneath the square.

But, Gunn offers advice to the new generation of truth-seekers:

“In front of City Hall there are plaques commemorating the steamships Savannah and Alabama. They say they celebrate the ‘first voyage of the grand adventure to Liverpool.’ Well, what was that “grand adventure” they’re talking about? It was slavery. Those were slave ships,” Gunn says.

“But that’s for another generation to take on.”

“This reveals why names matter," says the film's director, Caroline Josey Karoki. "We wanted to highlight the work of Sistah Patt and all the community. Because it is a community effort. We wanted to show what that looks like. We wanted people to see the struggle. To bear witness for those who maybe didn’t understand the process.”

Caroline says she had more than enough footage available from the years-long renaming effort to make her film much longer than its current 25-minute runtime.

But, she says, that would undermine the film's main purpose.

"This is a call-to-action film. It could easily have been 90 minutes. But it makes more sense as it is. This length keeps an audience engaged who are used to quickly going through reels on their phone. We’re trying to create a film that can convert an audience,” she says.

Referring to his own award-winning local history documentary, The Day That Shook Georgia, Longstreth says there's another advantage to shorter documentaries of this nature.

“My film was only 21 minutes – but that leaves more time for audience discussion afterward.”

Indeed, after this Thursday night's screening there will be a Q&A and discussion session with the filmmakers and community organizers, including Patt Gunn.